Impacts of Epidemics and Wars on Hotchkiss

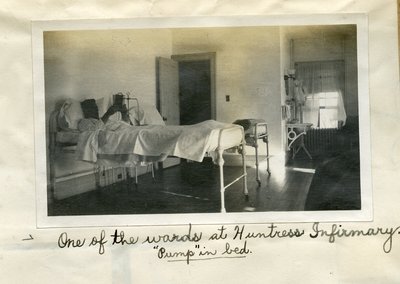

A ward bed in the Huntress Infirmary, in 1908, taken by Raymond Bowen, Class of 1908. Credit: Raymond Bowen ’08 Scrapbook, Hotchkiss Archives & Special Collections

Zoom classes did not seem like the future of the fourth marking period when students packed their belongings in early March. However, it is not the first time the school has had to change its style of learning.

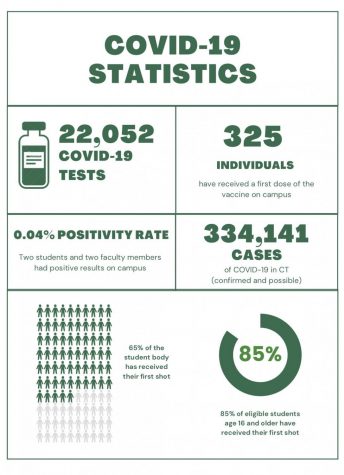

The school has successfully adapted during epidemics in the past that similarly altered students’ and faculty’s lives. A quarantine during a scarlet fever outbreak in 1904, a delayed school opening due to the 1918 Polio outbreak, a quarantine in 1918 due to the H1N1 flu, and the 1957 Asiatic Flu quarantine have all created similar extreme circumstances; however, modern technology accessible to students and faculty make distance learning and connection easier than in the past.

Scarlet fever, a streptococcal bacteria, was the first epidemic to hit the school after its opening in 1892. Dr. Jared Zelman, M.D. P’04, says that the acute virus can “[cause] severe disability, including heart and kidney disease, as well as neurologic problems,” any of which could lead to fatalities during that time period. As a result of three students contracting scarlet fever in 1904, headmaster Dr. Huber G. Beuhler dismissed students early for an extended Christmas vacation. However, students’ return to campus sparked another wave of the fever. A dorm was used to isolate infected students, who remained on campus, while healthy students were dismissed until March.

In 1905, scarlet fever struck again, and the school closed down for two weeks. After the epidemic, the school’s trustees realized the importance of having an infirmary on campus. In response, in 1906, the school constructed its first healthcare building, the Huntress Infirmary. After seven years of no cases, the scarlet fever infiltrated the community for the final time in 1913. Winter Break was extended for one month. The discovery of the antibiotic penicillin in the 1920s resolved the scarlet fever threat to the community and ceased to be a real threat in the U.S. by the 1950s.

The H1N1 influenza virus resulted in two epidemics: the 1918 Spanish Flu and the 2009 swine flu. The 1918 Spanish Flu had the greatest impact on the school’s community, due to the administration’s comprehensive response to the epidemic. As the 1918 Spanish flu hit Connecticut, the school allowed students to remain on campus, but employed quarantines similar to those of the previous scarlet fever outbreaks: rigorous measures such as banning all travel off the main campus and prohibiting anyone from outside the school community from entering were enforced. Mr. Thomas Drake, director of the Center of Global Understanding and Independent Thinking and instructor in history, said upon reflecting on the topic in his European history class, “Many of the practices that we have adopted were indeed used during the pandemic of 1918-1920. People were discouraged from sharing drinking glasses, etc. Hand-washing was promoted. In many cities, people were fined if they failed to cover their mouths and noses when coughing and sneezing. Schools and public gathering places such as bars, now extinct ‘dance halls,’ etc. were shut down in many [US] cities. Churches were not closed down. Even today, the restriction of church services is controversial. Sophisticated technology of our time [has] had positive and negative effects: communication is far more extensive and information (both accurate and inaccurate) can be circulated quickly.”

The 1957 Asiatic Flu led to quarantine measures similar to those used to combat the 1918 Spanish Flu, though they were less disruptive, as only weekend leaves were prohibited. Modern flu vaccines now provide protection against many strains of influenza, including those that led to these pandemics.

Just as widespread epidemics historically called for drastic measures at the school, wars have also greatly affected community life: World War I created a change in daily routines and habits, boys helped address local labor shortages during World War II, and the Vietnam War gave way to a change in overall attitudes and in the school’s moral environment.

World War I deeply led members of the community to live more frugally and raise money for war-related causes. The boys “drilled with the Hotchkiss Battalion in the afternoons,” according to the school’s WWI archive, and participated in military training over the summer as reserve soldiers. Many alumni and younger faculty volunteered to serve in the military and made significant contributions on the frontlines. Back on campus, 25 students formed a farming committee, dedicating themselves to using spare land to supply food for the community and aid local farmers. Community efforts raised 13,100 dollars for war bonds to support the country. In 1923, Memorial Hall was built in memory of the 22 students who sacrificed their lives during the war.

Twenty years later, World War II started, and once again, the school was heavily impacted. While younger students worked on farms to relieve the labor shortage, 1,596 alumni served in World War II, according to the school’s archives. Many students, such as Thornton H. Lytte ’44, a passionate skier, chairman of Mischianza, and a Harvard student, lost their lives in combat.

During the Vietnam War, many community members volunteered to serve in the military, however, dissident voices emerged within the student body. Students separated themselves into the “hawks,” who supported the war, and “doves,” who objected to the war, which divided the community. The community’s strong engagement in politics fostered a desire for changes and prompted many transformations on campus, including a more lenient dress code, relaxed meal attendance policies, and a greater emphasis on bringing racial and economic diversity to the school.

The many difficult, parallel circumstances recorded in the school’s archives serve to shine a light on the ends of this difficult situation. This information, provided by Ms. Joan Baldwin, curator of special collections, and Ms. Rosemary Davis, archivist and record manager, is accessible online here.