Re-Thinking Violent Crime in Chicago

Since the start of 2022, Chicago has already seen over 16,551 separate instances of violent crime. Not only is this one of the highest rates of violent crime among major U.S. cities, it is also a historically large number, even by Chicago’s standards (rates have jumped, in the same measurable time period, 35% from last year, 25% from 2020, and 11% from 2019). But this problem isn’t shared equally throughout the city.

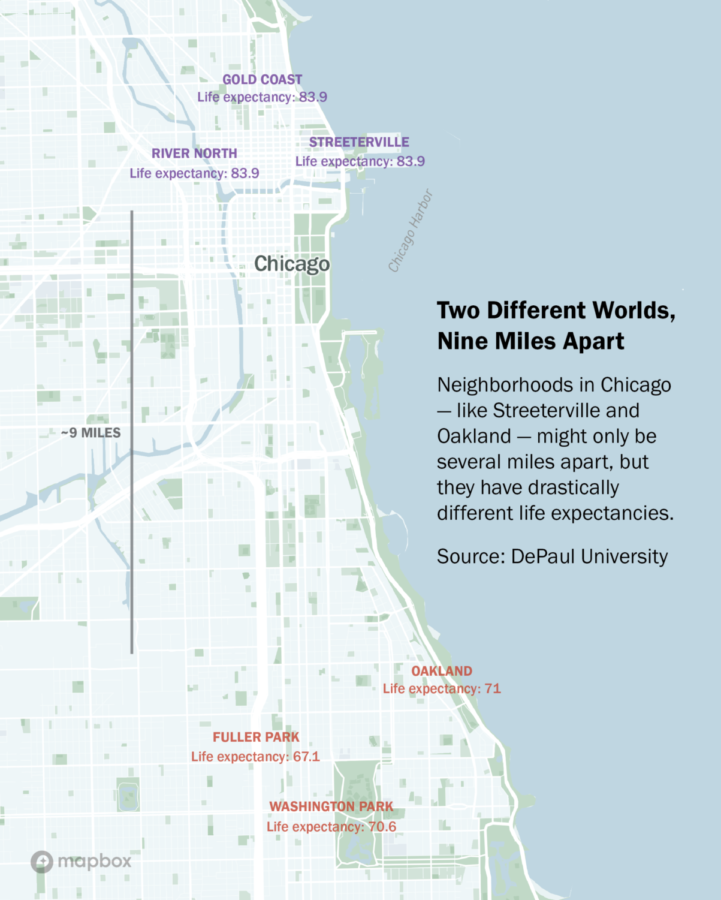

Within the city of Chicago lies 77 different neighborhoods. Among these are the extremely wealthy: Streeterville, the Loop, and Near North (all with life expectancies above 80; Streeterville: 90), and the impoverished: Englewood, Washington Park, and Fuller Park (Englewood life expectancy sits under 60 in some reports). Areas like Streeterville have some of the lowest rates of violent crime in the country, whereas, just nine miles due south, areas like Englewood have some of the highest rates. Those nine miles equate to an average of thirty years of added or lost life per resident. How is this even possible?

In the same way, residents of regions like Streeterville are in a positive feedback loop, with good schools, nutrition, policing, and healthcare spurring economic growth and leading to even better-funded schools, policing, and healthcare, areas like Englewood or Fuller Park are stuck in a negative feedback loop. Due to rampant gang violence, few employers want to move jobs in. As a result, residents are poorer, meaning they can afford less, thus causing suppliers to leave the area, taking whatever jobs remain with them. Finally, unable to find jobs with a livable wage, many residents have no choice but to join gangs in order to provide for themselves and their families. It doesn’t help that this process also leads to the creation of both “food deserts,” in which large swaths of land have no easily accessible grocery stores, and “health deserts,” where residents of an area have to travel great distances to reach any form of healthcare, including hospitals. Just this past week, Whole Foods announced the closing of their only Englewood location, simultaneously announcing the opening of multiple new locations in the Loop and Near North. Residents in the neighborhoods which lie in “food deserts” and “health deserts” are forced to rely on less healthy food, such as fast food, and inadequate medical care. The result, in short, is that rates of obesity and diabetes — which are among the most expensive conditions to treat in America — are both above the national average in Englewood. Without many high-wage jobs to pay for the necessary treatment of these diseases, even more Chicago residents are forced into a life of gang violence, thus continuing the vicious cycle.

This is not a problem that can be fixed by simply spending more on police, or even by subsidizing industry (as Whole Foods would tell you). The only solution to Chicago’s violence problem is not in the way of policy or politics. Rather, it is through economics and business.

Here is my solution: to start, organize a large-scale ceasefire of all gang-related violence in the city. Due to the volatility of the gangs throughout Chicago, this obviously isn’t a long-term solution, but you’ll have to stick with me. Next, begin building value-based care centers throughout the poorest neighborhoods of Chicago, in which healthcare is delivered by measure of the quality of care, not by the amount of care a doctor can give. This method drives better healthcare outcomes and oftentimes costs the patient less as well. Not only will this help create better, more affordable healthcare for residents, but it will also create jobs in the construction, operation, and staffing of these clinics, as there is currently a major shortage of nurses in the medical field. Now, here’s the tricky part: avoiding gentrification by staffing these facilities with Southside residents. If the jobs these clinics create are not going to the nearby residents of the area, then the intended economic growth will not happen. Instead, money will continue to leave neighborhoods like Englewood, traveling north to whoever is actually working in these clinics.

Assuming the jobs do end up in the hands of nearby residents, this plan is profitable for all parties. Southside residents get high-paying, livable-wage jobs, and they receive high-quality, low-cost healthcare. In addition, clinics that move into the area get paid more, because when life expectancy is already at 60, almost anything is an improvement in quality of care. In one fell swoop, the Southside’s negative feedback loop is replaced by a positive one. Now that residents are being well-paid, employers want to move in, bringing more jobs and money, improving nearby schools, etc.

As Lori Lightfoot, Mayor of Chicago, put it: “If we truly want to end the cycle of community violence once and for all … we must get to the root causes of violence. We can and we must invest our way out of this problem.” Since she took office in 2019, violence in Chicago has reached 25-year record highs, with the only notable policy change being an increase in the Chicago Police Department’s budget. Time for a different approach?