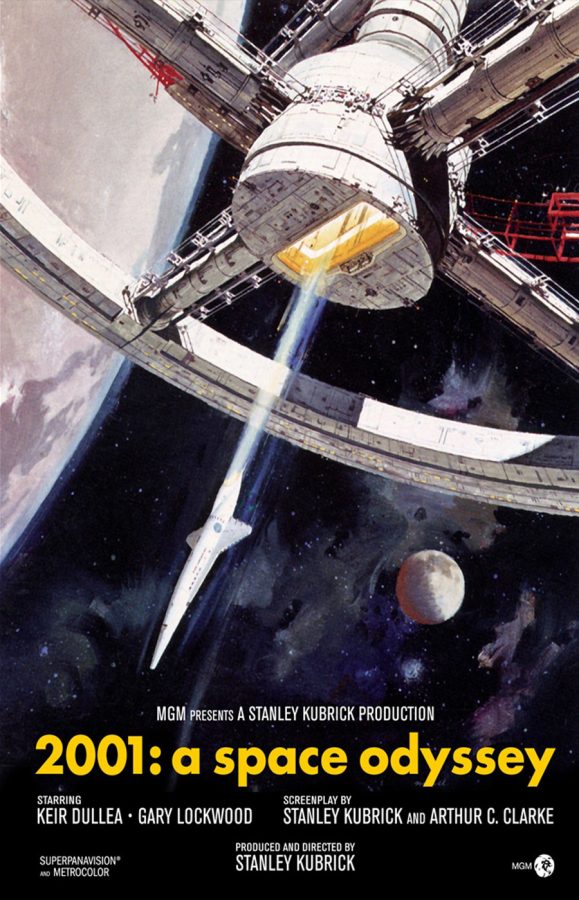

Beneath the Base of the Monolith – An Analysis of 2001: A Space Odyssey

A mysterious recreation of the Monoliths from the film was recently found in the Utah desert.

It has been more than half a century since the release of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, yet the majestic sci-fi film still leaves its audience perplexed today. This time-bending film revolves around the Monoliths, towering slabs of metallic entity. The film was ahead of its time. It differentiates itself from other sci-fi films of its time not only by the self-awareness and progressiveness in the ideologies of our existence, but also by the cinematography, production design, and the storyline’s sheer depth. It predicted modern technologies such as iPads and artificial intelligence, anticipated the struggle between man and machine, and inspired numerous modern sci-fi classics.

Kubrick presents the film in four parts, which progress chronologically over several millennia, from when apes walked the earth to the age of inter-solar system travel. Through this time, evolution takes place in many shapes and forms. The most noticeable changes, however, are the technological advancements. In Dawn of Man, the first chapter, prehistoric hominids discover weaponry in its most organic form – bones – and capture control over a watering hole. In the second, untitled chapter, set on the Fifth International Space Station, humans follow the same prehistoric ape-like mindset, using futuristic technologies to prevent opponents from reaching a new possible advancement in technology. In the seamless transition between the aforementioned chapters, the audience also witnesses the development of technology from bones to space shuttles, and later from barbaric cries to instant radio-communication with a supercomputer millions of miles away. However, with these astronomical developments in technology, the basic instincts of humans remain unchanged. The film poses the question: does the evolution of technology really represent evolution of humankind?

Kubrick depicts the limitations and feebleness of the human brain through the interactions between humans, the Monoliths, and technology. In the second chapter, the fear and curiosity in pioneering scientists stimulated by the discovery of Monoliths are almost identical to the reaction of the apes to the same structure. As a group of leading scientists approaches the Monolith discovered on the dark side of the moon, they admire it with amazement and fear. In the final chapter, Jupiter and Beyond the Infinite, in a modern baroque room trapped in a void of time, the protagonist in the latter half of the film grasps at the Monolith with his very last breath. In the third chapter, Jupiter Mission, the “fool-proof” AI capable of “[reproducing]… most of the activities of the human brain… with incalculably greater speed and reliability” (2001: A Space Odyssey), the HAL 9000, proves to be more human than any of the protagonists. Despite lacking human form, HAL displays profound emotions of pride and regret more powerful than either of the astronauts during the journey to Jupiter. When HAL malfunctions, the astronaut’s first instinct is to completely terminate it.

The Monoliths in this film prove one hard truth to our evolution: no matter how advanced humans become, when emotions are triggered, we always resort to our root primal instincts, disregarding all technological advancements. There is truth in this. We often hear the phrase “emotions are what make us human,” but it could also be what’s preventing the next phase of evolution, a jump as big as apes to humans. In a year full of chaos, the artist behind the mysterious recreation of the Monolith (recently found in the Utah desert) is possibly commenting on the accuracy of the statement that Kubrick made through this cinematographic masterpiece.