Protect Innovation in Silicon Valley

Facebook, Instagram, Google, the iPhone – these technologies have become a necessity in the lives of people, connecting billions across the world. Their widespread usage has given Silicon Valley companies immense authority over the private information of millions of users and a prominent position in the technology market.

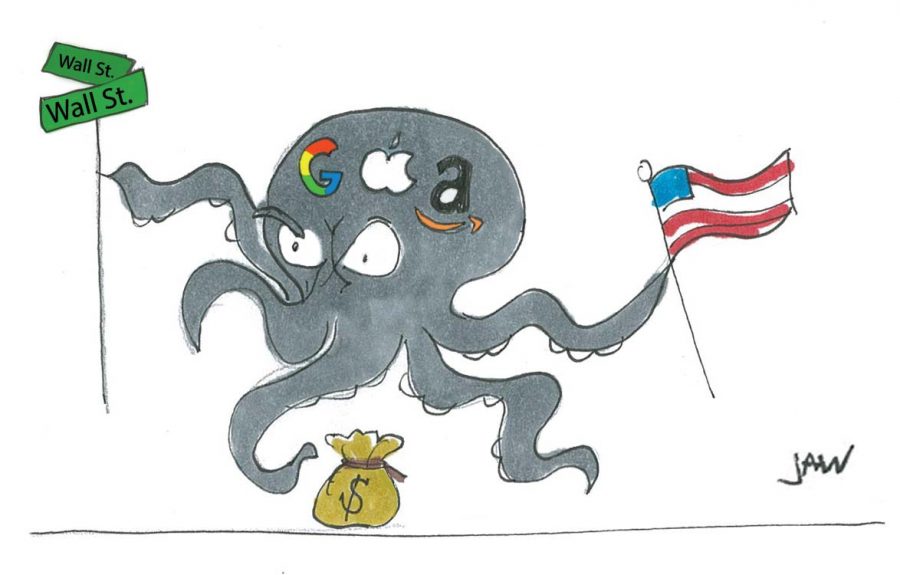

As a result, regulations on the power and influence of “Silicon Valley Monopolies” – namely Google, Apple, and Facebook – have become an area of heated political debate. In the recent Democratic Debate, all candidates who spoke on the issue unanimously agreed that some intervention was necessary, because these large companies should not be able to access private information. Candidates varied in terms of the degree and method of regulation they believed was necessary, however.

Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) shared her plan to “break up Big Tech,” stating that the same individuals who are the “umpires” of the industry can’t also be competitors in it. Senator Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) called the tech boom “another Gilded Age” and claimed that monopolies lowered prices to drive out competition. Andrew Yang claimed that competition wasn’t the answer and proposed an alternative solution of giving consumers more power over their data.

Essentially, the idea that monopolies are harmful is based on two premises: monopolies have too much political power and they have an advantage in competing against other companies.

Firstly, tech monopolies do have a lot of power; however, this isn’t necessarily bad for people. Traditionally, the notion of a “monopoly” refers to a company that dominates a specific industry and can profit by charging high prices. This creates a stagnant market in which there is no development, because competitors are driven out and customers have no choice but to pay higher prices. But this clearly isn’t the case for tech companies. They generate profit by creating better technology and advancements for society – every time a new “monopoly” emerges, it generates a new market and category of products. Naturally, this ensures that continuous development is taking place, along with a constant ‘shift’ in the corporations that dominate the market.

Secondly, it is true that monopolies have an unfair advantage over other corporations. However, this advantage is no longer in the form of physical resources – it is in the form of customers’ data. This is precisely why the notion of “breaking up the tech monopolies” is gaining support. If the corporations were broken up, they would not be able to share personal information amongst different platforms that belong to the same company.

Competition within platforms has also been an area of ongoing controversy. Last year, Google was fined five billion dollars for presenting its own price comparison engine over other websites, and Amazon allegedly lowered the prices of baby products by almost 30 percent in an effort to pressure Quisidi into selling its site to Amazon. These are all examples of how Silicon Valley corporations gain an unfair advantage over other competitors through their platform.

This has been a major reason why the idea of separating the platform and other services of the company have gained support. Nevertheless, the current antitrust laws that allow both the government to conduct investigations and impose fines and other companies to sue these platforms are already sufficient to regulate such violations. Though there is an incentive for the platforms to prioritize their own products, should the government provide stricter regulations and more frequent investigations, it will be enough to check and balance such motives.

But do we really need to break them up to ensure competition and customer privacy? A far better solution, and one that is easier to execute, is giving consumers the right to control their personal information. This way, people could opt-out of putting their personal data into the hands of corporations and be cognizant of which platforms are in possession of their data while other smaller corporations have a more equal starting line.

It is undeniable that there are certain problems that arise from large corporations dominating certain industries. Yet it is also evident that “breaking up” these companies is more political posturing than an actual solution. In fact, the government’s being able to decide which companies need to be broken up gives the government the power to decide which companies would be the “winners” and “losers” of the market, creating more potential areas of abuse.

Instead of a blanket policy that only targets specific companies, companies should address the problems directly by providing users with the right to control their own information and preventing injustices within platforms.