Brexit, the European Union, and All Things Broken

On Thursday, June 23, 2016, the United Kingdom held a referendum that allowed British citizens to choose whether they would like to remain in or leave the European Union. A majority vote chose to leave and the process of Brexit (British Exit) was set in motion.

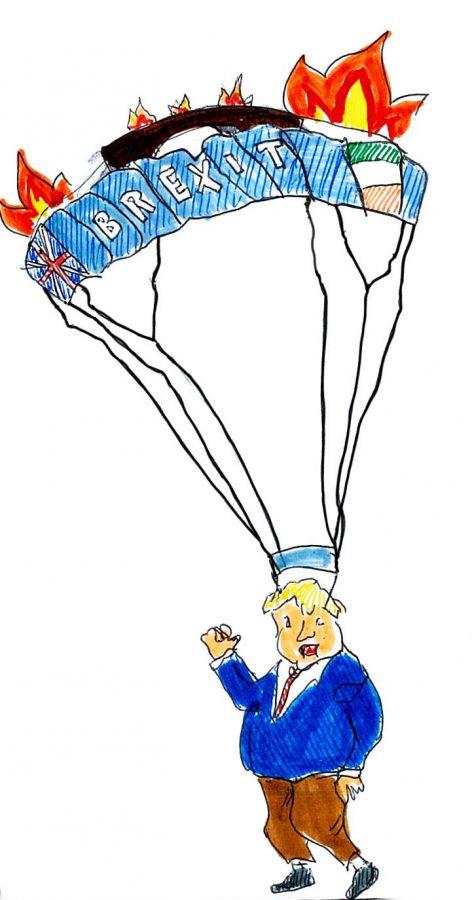

Before the first ballot was cast, problems arose with disinformation surrounding the vote itself. Many citizens who thought they wanted to leave were not well-informed enough about the repercussions of that choice. Voters were not thinking about drastic economic changes, trade complications, and political backlash; instead, many Britons on the day of the referendum were motivated by xenophobia, immigration concerns, and misinformation. The “Leave campaign” – chaired by now-Prime Minister Boris Johnson – drove a bus around the UK, falsely claiming the UK sends £350 million to the EU every week, which he said could instead be directed to the UK’s public healthcare system.

Before the vote, British politicians such as Prime Minister David Cameron should have educated the UK about the negative consequences that would ensue if the UK were to leave the EU. Negotiations about how the UK would leave the EU were only discussed following the referendum – had a plan been formulated before the vote, Britons would have been able to know more concretely what they were supporting or voting against. This failure to communicate was a mistake, as it has sent the country spiraling into a confusing predicament.

Following the referendum and a victory for the Leave vote, Prime Minister Cameron resigned. He had proposed the referendum with no belief that the UK would ever vote to Leave. So, when Theresa May became Prime Minister, she had to devise a plan from scratch. She handled the affair poorly to begin with, making the decision to leave the EU within two years as a way to pressure the British Parliament. This commitment severely restricted her negotiating power with the EU. What she should have done, but didn’t, was to formulate a deal for how the UK should go about leaving before initiating the two-year limit, so that the UK would at least have a safety net while deliberating. Therefore, the deal that Prime Minister May did propose was considered unsatisfactory. Many of the people felt they would rather have no deal at all than embrace hers.

There really was no alternative. She could have ignored the results of the referendum, but that would be seen as utterly undemocratic. She could have just left the EU without a deal (which is what now-Prime Minister Johnson is championing), but that would be disastrous for the economy, borders, and foreign relations.

There was also one element that stalled negotiations to a halt: the backstop. Northern Ireland is one of the four countries that make up the UK. Unlike England, Scotland, and Wales, however, Northern Ireland is a seperate island. One of the principal reasons why Britons voted to leave the EU was to exit the EU customs union. However, Northern Ireland would have to create a border between itself and Ireland, a seperate country that remains a

member of the EU. That cannot happen under any circumstance. The past division between the two nations resulted in The Troubles, an ethno-nationalist conflict starting in the late sixties and ending in the late nineties in the Good Friday Agreement. The agreement said that a hard border would never again divide Ireland and its northern sibling. Yet if there cannot be a hard border between Ireland and Northern Ireland in a Brexit agreement, could the border be between Northern Ireland and Great Britain? That would be like having a border between Texas and the rest of the United States. That leaves the backstop, which keeps Northern Ireland in the EU customs border, allows free movement between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK, and kicks the problem down the road as it does not truly remove the UK from the EU. Those are the only three options, limited not by political will but geography.

The best thing the UK can do is hold a second referendum so that citizens can vote knowing the true consequences of what each choice represents. Rather than wasting more time trying to figure out a way to repair this mistake, it would be more sensible to hold another vote. If the majority still wishes to leave, knowing all that it entails, then so be it. At the very least,it will put an end to the chaos that currently consumes the British government.

Contact Camilla Fritzinger at

[email protected]