In Los Angeles, it is raining fire. Wildfires have destroyed over 12,000 structures, displacing over 150,000 residents and killing at least 27 people. More than 60 square miles have been torched. Analysts predict the total damages will exceed $250 billion, making the wildfires the second most costly natural disaster in U.S. history—exceeded only by Hurricane Katrina.

We Angelenos are submerged in despair. So why aren’t more people in our community talking about it?

Our school has exhibited a surprising display of indifference toward the fires. Of course, there have been passing questions about the well-being of my family and the state of my house (which fortunately has not been consumed by flames). But on a broader level, I have witnessed a shocking level of apathy in our community.

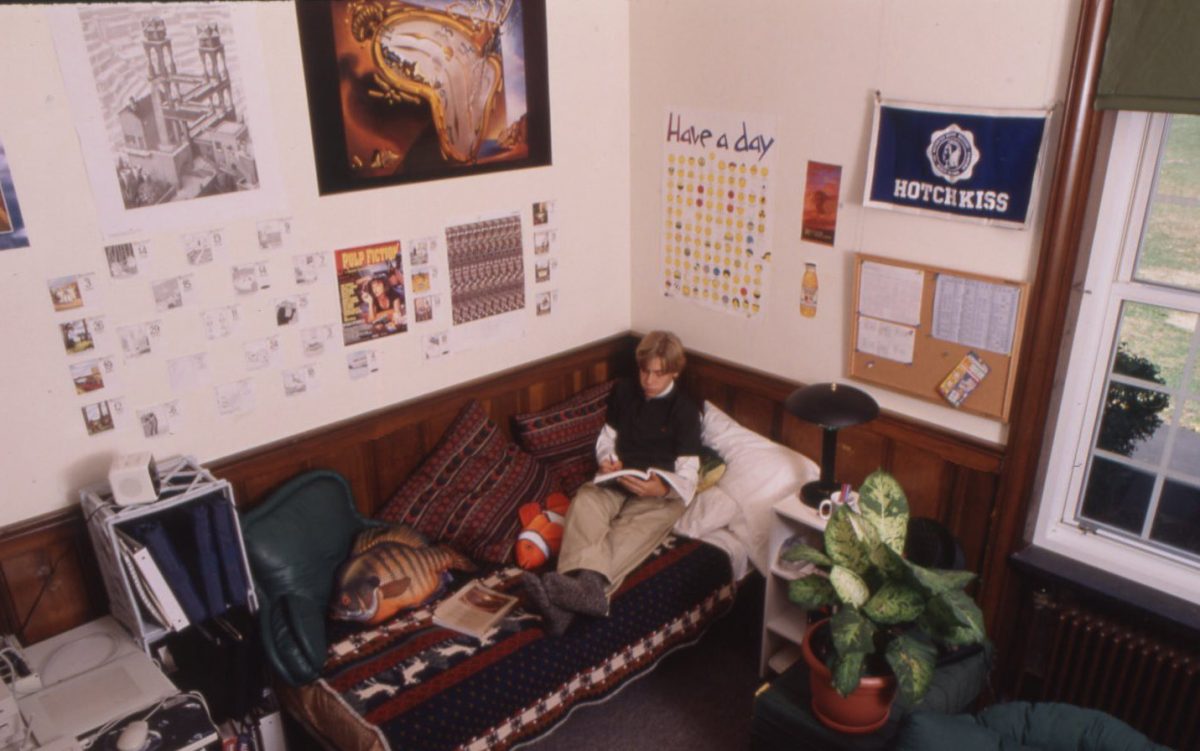

I’m not asking people to stop their days to engage in a collective meltdown. But I am also a little disturbed by just how real the “Hotchkiss bubble” is: how our geographic isolation and position of privilege makes it very difficult to meaningfully converse about things beyond our direct experience.

The prognosis for today’s youth that we hear all the time is impressively bleak: we are afflicted with crippling addictions to our devices and coddled by our parents; we are more stressed, anxious and depressed than any recent generation, as evidenced by our record-high suicide rates; we are pitifully immature on a mental and emotional level, but too quick to embrace the social rituals of adulthood; we are overexposed to stimulants but underprepared for reality.

However, these diagnoses are absurdly reductive. They dilute one of the most ideologically and culturally diverse generations

the U.S. has ever had and are needlessly defeatist. I believe we can still crest the wave of socio-political chaos that is threatening our collective futures. But I also believe there is a chance we will not escape the self-pitying narcissism instilled in us by social media, will not look beyond ourselves to see the destruction slowly encasing our society, will not escape a future of useless outrage or resigned passivity.

I have come to realize what our generation is really lacking: empathy. It’s not our fault— at least not entirely. The profit models which have established today’s attention economy are fundamentally designed to turn our focus on the self. Social media, for instance, encourages people to express political solidarity by reposting inflammatory headlines on their own profiles; this implicitly filters major current events through a lens of egocentrism. We do not care unless we are personally impacted.

I too find it very difficult to forge an emotional response to the endless maelstrom of images and headlines and stories that fill my inbox each morning. There is something about the massive influx of fatalistic coverage that makes it impossible to parse through each story and view the people within them as real people—not just characters populating an apocalyptic alternate universe. And it was only when I was directly impacted by disaster (via the wildfires) that I actually gave a thought to the detachment with which our society treats global suffering.

It is far too easy to fall into the trap of indifference. A subconscious mantra of “at least it’s not me” or “that must really suck”—is all too common, and for good reason. But we have to remember that there are real people on the other side of our screens. Of the many victims who lost their homes to the fires in L.A., two are my aunts, one is my uncle, and seven are my close family friends—not to mention one of my friends who discovered their house was gone by watching it burn on live television.

Which is to say: the sensationalist headlines, the photos of burned buildings, the stories of death and loss and grief—it’s all happening to someone, even if that someone isn’t you.

The fires have catapulted us into a grim vision of a destroyed climate. What now seems like an isolated extreme will reveal itself as the new norm. We must not dull our horror with the anesthetic of inaction. We carry the weight of social responsibility, and it is high time that we mobilize the public consciousness to find a way to connect with one another— and to care about the future.